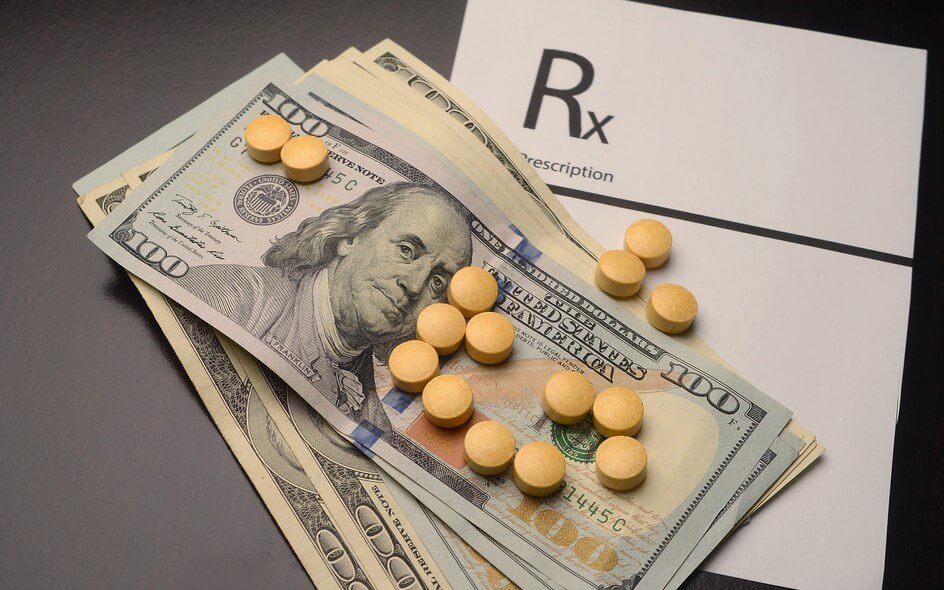

With health care a top issue for American voters, Congress may actually be moving toward doing something this year to address the high cost of prescription drugs.

“It’s not sustainable. The country needs more problem-solving for the common good and not the corporate bottom line.”

President Donald Trump, Democrats trying to retire him in 2020, and congressional incumbents of both parties all say they want action. Democrats and Republicans are far apart on whether to empower Medicare to negotiate prices, but there’s enough overlap to allow for agreement in other areas.

High on the list is capping out-of-pocket costs for participants in Medicare’s popular Part D prescription drug program , which has a loophole that’s left some beneficiaries with bills rivaling a mortgage payment.

The effort to cap out-of-pocket costs in Medicare’s prescription plan is being considered as part of broader legislation to restrain drug prices.

Limits on high medical and drug bills are already part of most employer-based and private insurance. They’re called “out-of-pocket maximums” and are required under the Obama-era health law for in-network services. But Medicare has remained an outlier even as prices have soared for potent new brand-name drugs, as well as older mainstays such as insulin.

“The issue has my attention,” said Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Iowa, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, which oversees Medicare. “Out-of-pocket costs are a concern of ours, particularly at the catastrophic level.” His committee has summoned CEOs from seven pharmaceutical companies to a hearing Tuesday.

While Grassley said he hasn’t settled on a specific approach, the committee’s top Democrat, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, recently introduced legislation that would cap out-of-pocket costs at about $2,650 for Medicare beneficiaries taking brand-name drugs. One co-sponsor is Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Democratic presidential candidate.

In Des Moines, Iowa, retired special education teacher Gail Orcutt is battling advanced lung cancer due to radon exposure. Although she has Medicare prescription coverage, she paid $2,600 in January for her cancer medication and will pay about $750 monthly for the rest of the year. She said it cost more last year for a different drug — $3,200 initially and then about $820 monthly.

Someday her current drug may stop working, said Orcutt, and then she’d have to go on a different medication. “What if that is two or three times what I’m paying now?” she said. “It’s not sustainable. The country needs more problem-solving for the common good and not the corporate bottom line.”

At a recent House Ways and Means Committee hearing, three expert witnesses with varied policy views concurred on limiting drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries. “This is still the only program that does not provide that protection to its beneficiaries,” testified economist Joe Antos of the business-oriented American Enterprise Institute. The House committee also oversees Medicare.

Before the hearing, the committee’s chairman and top Republican released a joint statement unusual in polarized times: “We agree that the time is now to take meaningful action to lower the cost of prescription drugs in the U.S. health care system,” said Reps. Richard Neal, D-Mass., and Kevin Brady, R-Texas.

John Rother of the National Coalition on Health Care is a longtime participant in national health care debates, and his organization represents a cross-section of interest groups. “There is a common recognition of a problem, and also a sense that they want to move something this year,” he said.

At issue is the Medicare prescription benefit’s “catastrophic” protection. Experts say it was intended as a safeguard but isn’t working that way, either for beneficiaries or taxpayers.

Catastrophic protection was enacted before the advent of drugs costing $1,000 a pill. It kicks in after beneficiaries have spent about $5,100 on medications, under a complex formula.

After that, the beneficiary is only responsible for 5 percent of the cost of the medication, and taxpayers’ share rises to 80 percent. The patient’s insurer covers the remaining 15 percent.

The problem for beneficiaries is that there’s no dollar limit to what they must pay. For example, 5 percent of a drug that costs $200,000 a year works out to $10,000.

Numerous experts also say there’s a problem for taxpayers.

Generally, the Medicare prescription benefit is financed with a mix of government subsidies and beneficiary premiums. But in the catastrophic portion, most of the bill is passed directly to taxpayers. That neutralizes the incentive for insurers to negotiate lower prices with drugmakers. Catastrophic is the fastest growing cost for Medicare’s Part D.

The administration has supported an approach recommended by experts that would shift most of the responsibility for high-cost medications onto insurers, while capping what beneficiaries must pay. That would force insurers to seek lower prices. But it may well raise premiums.

About 3.6 million Medicare beneficiaries with Part D coverage — or 9 percent — had “catastrophic” costs in 2015, according to the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. Of those, about 1 million had to pay their share in full because they didn’t qualify for financial assistance provided to low-income beneficiaries.

“This affects people with serious conditions such as cancer and multiple sclerosis,” said Tricia Neuman, a Medicare expert with Kaiser. “People on Medicare can still face huge expenses for their medication because the Medicare drug benefit was designed without a hard cap on out-of-pocket costs.”

© The Associated Press. All rights reserved.