The current lineup of Federal Reserve officials have almost unanimously favored gradual increases of interest rates over the past two years. But that could be about to change as President Donald Trump’s tax cuts begin to lose some steam.

So far, record-low unemployment and strong economic growth numbers have led to the Fed to continue its monetary tightening, pushing the benchmark interest rate to a 2 percent to 2.25 percent range, pushing up mortgages and the cost of borrowing in general.

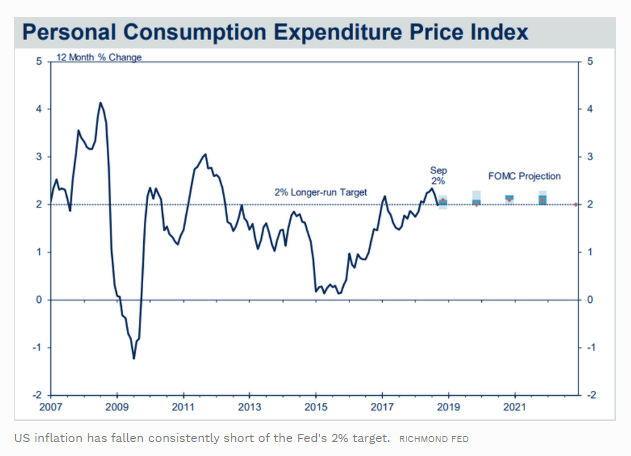

All signs point to the Fed holding off on the next rate hike until December while inflation has yet to really catch up to the Fed’s 2 percent target. Wage growth has lagged though a recent uptick is encouraging, and most forecasters don’t see major increases in inflation or wages in the near future.

Per Forbes:

“Haven’t they spotted that wage growth, while improving, is still modest?” said David Blanchflower, a former Bank of England official, in an interview. “Ultimately we wait to see the whites of the eyes of inflation then we know what to do.” The Fed’s congressional mandate is to pursue maximum employment as well as low and stable consumer prices.

The chart below shows how inflation correlates to the Fed’s target over the past several years.

The U.S. GDP got a strong bump from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act during the past two quarters, hitting 4.2 and then 3.5 percent, respectively. But there is debate in and outside the Fed as to how long the tax cuts will boost the GDP, especially since gridlock will likely come to Congress with the Democrats taking the House.

Michael Feroli, chief US economist at JP Morgan, told me he still thinks the Fed will hike rates five more times before taking a breather – once in December, and another four times next year.

Still, he said, “by the time you get to September of next year then you have a very vigorous debate about whether going into an actual restrictive territory at that point.”

Feroli, a former Fed economist, sees central bank officials converging around the 3% mark as the “neutral” rate of interest–one that neither bolsters or softens growth. So effectively, the central bank is just three quarter-point hikes away from that range.

That’s when the Fed will likely pause.

In his first public remarks in the No. 2 role, Clarida said: “If the data come in as I expect, I believe that some further gradual adjustment in the federal funds rate will be appropriate.” That contrasted subtly but importantly with the official FOMC statement language, which reads: “The Committee expects that further gradual increases in the target range for the federal funds rate will be consistent with sustained expansion of economic activity.”

The addition of “some” and the change to “adjustment” from “increase” may seem insubstantial, but Fed-speak is a game of incremental addition and subtraction.

Another issue is now that inflation has caught up to its 2 percent target is how high the Fed will allow it to go. Officials say they want to stay near that goal but also to hover as much above it as below.

However, Feroli said, the apparent strength of the labor market, with the headline jobless rate near historic lows of 3.7%, will make Fed officials reticent about allowing the inflation rate it targets, the personal consumption expenditures index, climb much above 2.25% or so.

“It’s easy to say symmetry, and if you were at 2.3% and the unemployment rate were 5-1/2% that would be one thing. I kind of think in a tight labor market environment about 2.25% starts” to rattle policymakers’ nerves.

This could prompt the Fed to further tighten more than it would normally go, but it’s not as likely due to the gradual drag on the economy of inflation and the ongoing trade war with China.