As we enter the middle part of the summer, we also enter the beginning of Q2 earnings season, and this all adds up to fun times. The equity markets puttered around a bit this week and between the “wait and see” on a China trade deal and the “wait and see” on Fed accommodation, earnings ought to be the major story for the next couple of weeks.

In the meantime, I really tried to use this week’s Dividend Cafe to unpack some foundational things about the U.S. economy. What does the yield curve tell us about a recession? Why has the Fed become so accommodative to capital markets (there is an answer!)? What would make someone want our Fed to not be independent? What do pension funds tell us about the future of asset allocation? What can government spending tell us about the state of economic growth?

If all of these questions are addressed this week, and they are, plus a few MLP and Brexit comments to boot, can you see why I am so excited to have you join me in the Dividend Cafe?

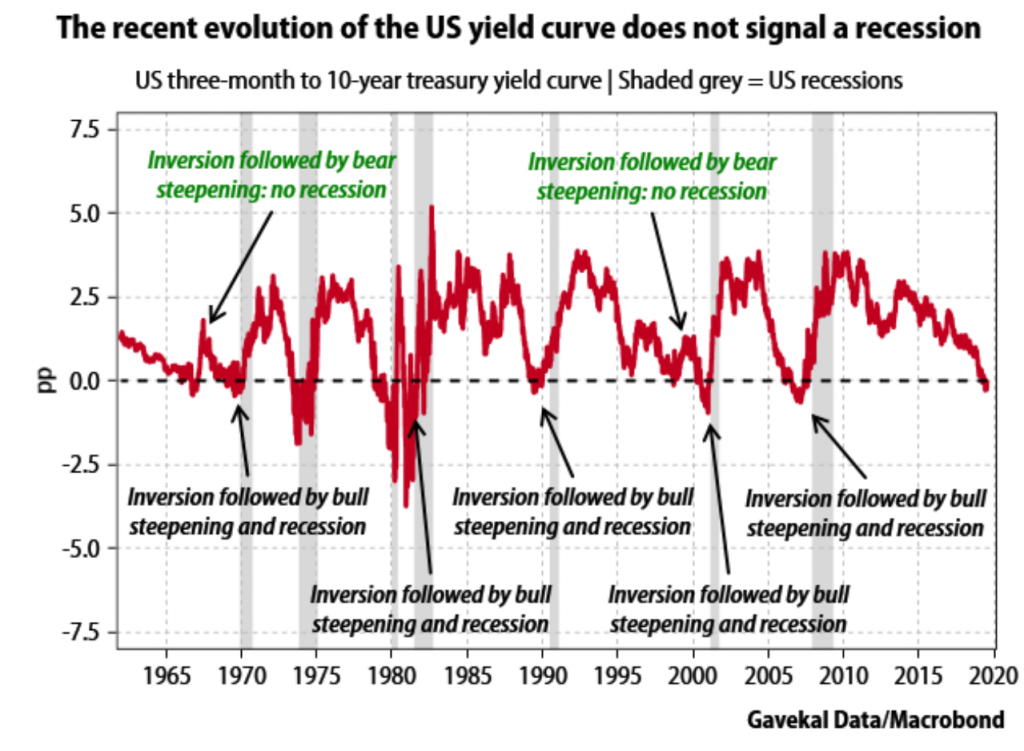

Yield curve watch

Don’t look now, but that 3-month/10-year yield curve inversion has nearly disappeared. And while the 2y/10y got as flat as can be, it stubbornly refused to invert throughout. This is a case of Fed guidance/indications being a policy tool in and of itself, and not just pointing to actual policy tools.

Our view is that the Fed’s dovish switch will anchor the short part of the yield curve down, and that just basic modest improvement in growth outlook will push the longer part of the curve up a tad, meaning we will experience a steepening yield curve for the remainder of 2019. There are precedents where this chain of events ended up working out very well (1998 is the most historically interesting example), and there are precedents where this led to recession. History offers no lesson on how this particular situation will play out.

The math of it all

Did you know that the median assumed return for state pension funds is 7.5%, across all 50 states? (Yes, that means plenty use an assumed return rate higher than 7.5%). And I am sure you know that the 10-year Treasury bond yield is presently 2%. So any money in bonds in the multi-trillion-dollar pension system in our country is forcing them to need a higher return from their stock and alternatives portfolio to average 7.5%. Since you can’t will your way to a certain return in risk assets, what options exist for pension managers who need a 7.5% return to meet expectations? Simply put — it forces them to move money out of bonds into stocks (and alternatives) as the present asset allocation will not facilitate the returns they have to get.

Now, stocks may not achieve it either, but at least they have a chance. They know the yield on bonds. The math requires more money into stocks. And this is the United States pension system where we do have some positive yield in our bond market! There is $13 trillion in global bonds around the world with a negative yield. How do they get to their discount rate with a negative carry in bonds?

This may prove to be the biggest driver of equity valuations for years to come — the pension realities here in the United States and around the globe, attached to the math of low (or negative) bond yields.

Should the Fed be independent?

This is actually one of the easiest things for me to answer without having to tip-toe around the politics of it (I am not sure if I ever feel the need to tip-toe around the politics of much). I happen to be pretty turned off by President Donald Trump’s jawboning of the Fed on Twitter and elsewhere, and I have never had any problem publicly saying so when I believe the President is wrong about something (or when I feel he is right about something). So, in this case, I do disagree with the methodology, and at the same time, don’t believe it is particularly controversial to say that:

- A. The Fed has never been all that independent of political pressure here in the states (other politicos were just more subtle about it), and much more importantly …

- B. Pretty much no other nation even pretends their central bank is independent of their political system

Our Fed is not fully “independent,” but certainly no one else’s is, and that matters right now. The ECB is about to re-ramp Quantitative Easing. I mentioned previously that $13 trillion of assets around the globe presently trade at a negative yield. Global central banks, tied to the hip of their political leaders, have found new monetary policy tools previously thought incomprehensible. But it is not our central bankers we look to make sure we are globally competitive; it is our politicians (Dear Lord). So “independence” is a pipe dream, even if we do agree that the twitter trolling is unbecoming.

Why the Fed went dovish, part 35

Few topics have generated more attention since Jan. 4 of this year (in the financial media, but also in these Dividend Cafe pages) than the Federal Reserve’s significant about-face from a hawkish, tightening monetary posture last year, to the total opposite (in tone, rhetoric, and action) this year. We have talked about inflation running beneath their target rate for it (I spoke about this on Neil Cavuto this week). We have talked about the concept of an “insurance cut.” Many have talked about the political pressures around all of this.

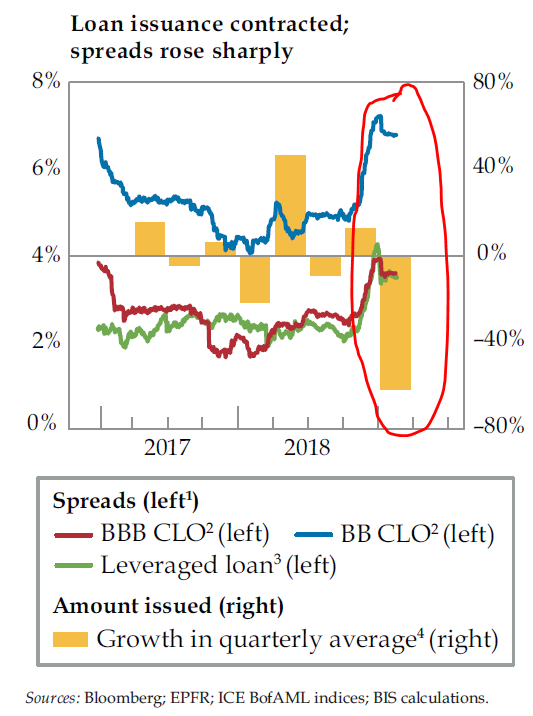

But there is nothing more clear to me than what happened in the credit markets late last year to explain why the Fed feels the need these days to channel their inner Bernanke/Yellen … Bond market liquidity dried up in Q4, it got very little press, but I believe it scared the you-know-what out of central bankers. Bond issuance dried up. High yield outflows skyrocketed. And credit spreads rose. That milieu was, in my opinion, the major factor driving the Fed’s change of thinking. They got a look at what “unwinding” the post-crisis accommodation would mean to the U.S. economy (primarily in terms of corporate credit and how the economy has become addicted to it), and they chickened out.

Valuation caveat that bears repeating (for the last ten years, and the next ten)

There is no question that risk assets have historical averages around how they trade (multiples of cash flow, multiples of earnings, etc.). These valuation metrics on an absolute basis and a relative basis do matter. And I have gone to great lengths in the Dividend Cafe to discuss valuation, and what things mean, and what things don’t mean, etc. So in what I am about to say, there is no room to interpret it as a suggestion that valuations do not matter. They do. But it is also equally true that evaluating valuations requires a reference – something the asset is being valued against. And financial markets have always framed valuations around a comparison to a risk-free rate. Right now, we know that the P/E ratio of the S&P 500 is roughly 17.6x (on a forward basis). But we also know that corporate bond yields and treasury bond yields are significantly below historical averages, not merely suggesting but frankly mandating that risk assets warrant a premium to their historical valuations.

Financial types come up with all sorts of ways to evaluate the “earnings yield” of the market relative to the bond market. The Fed has always loved the “Fed model” where the bond yield is dividend into the earnings yield of the market (earnings divided by price instead of the P/E ratio which is price divided by earnings). This allows for some sort of comparative number where the earnings yield is evaluated by the number that frankly drives financial markets – U.S. bond yields.

Valuations say what? A Summary:

- The S&P 500 is slightly above its historical average of valuation on an absolute basis

- Valuations have never been a “timing” tool

- The present valuations of risk assets relative to the comparative risk-free rate are significantly below historical averages

- There is no way to assess what this means about next month or the month after — so do not over-think it or over-act on it. Our asset allocation weightings account for these market realities.

Globalism for the anti-globalists

A recent Chamber of Commerce survey suggests that the tariffs levied so far against U.S importers of Chinese goods are succeeding at getting manufacturing moved out of China … to other Asian countries. Just 5.5% say they are considering or have considered moving their manufacturing back to the United States. About 10.5% have said they are considering Mexico as an alternative plan. And a stunning 25% have said they are looking at other Southeast Asian countries as a manufacturing hub. The vast majority are maintaining their Chinese presence.

Brexit watch

We are a few months away from what is supposed to be the deadline for the Brexit process (Britain’s exit from the European Union). Boris Johnson looks like the overwhelming favorite to be the next Prime Minister, and he has indicated rather unequivocally that he will let a so-called “no-deal” Brexit happen if need be. Of course, many wonder if he is posturing in saying that to get the concessions that need to happen or if he really means it.

I have been studying this entire process economically, politically and strategically since 2015, and particularly this year have become intrigued by the strategic posturing of it all. Ultimately, I am convinced that should a “no-deal” Brexit happen, the loser will not be Britain, but rather the losers will be European exporters, most profoundly, Germany. I reckon the sterling pound to be deeply under-valued, and while I always maintain a healthy respect for the potential of short term market disruption, I do not fear any fundamental, sustained distress out of this next Brexit iteration.

My repeat question (uttered by yours truly dozens of times since the Brexit referendum vote of 2015): Please name the last time freedom and liberty were increased, but prosperity decreased. You will search in vain.

Midstream MLP Mania

For those already familiar with all the vocabulary, I may use here, forgive me. But for those who find the clarifications useful, when I refer to the “midstream” sector of the energy industry, we are primarily referring to the pipeline companies that transport oil and gas from the point of production to the point of distribution. When we say “MLP,” we refer to a “Master Limited Partnership,” which is just a business structure that many of the oil and gas pipelines used/use for tax reasons (more and more of these companies are converting to traditional corporations). So “midstream” and “MLP” and “oil and gas pipelines” are almost always being used synonymously in these Dividend Cafe pages.

And with that said, a quick mid-year update is in order for the midstream sector that is a heavy conviction thesis at The Bahnsen Group. Up about 20.5% on the year (total return), the sector has enjoyed six positive weeks in a row, which really does not happen very often (only the second time in the last five years). The yield spreads remain way above historical averages, and the financial metrics have improved substantially across the space. The natural gas liquids space is particularly showing signs of living up to its growth potential.

The encouraging thing for investors here is not merely the returns achieved thus far, but the fact that even after these returns, the sector remains one of the very few demonstrably under-appreciated, under-valued opportunities out there!

Interest rates … rising?

I am in the camp that believes the Fed will (not should, but will) lower the fed funds rate by a quarter-point this month. We have seen longer-dated bond yields drop significantly this year. So will rates go lower still when the Fed cuts?

Not if history is any guide.

In all four of the last “rate cut” cycles the ten-year treasury bond yield has risen eight months after the Fed began its first cut in an easing cycle. Why? First of all, it doesn’t matter — history is what it is … But secondly, markets are always and forever discounting what they believe about the future. If an investor believes short term rate manipulation will either stimulate growth or inflation, they will demand higher interest for longer-term commitments. That is sort of the point for the Fed here — to steepen the yield curve. My point is — do not assume the pedestrian idea that as the Fed cuts their short term interest rate, so must all other interest rates go down with it. It is not only untrue economically; it is untrue historically as well. Theory, and practice!

Not much more to it than this

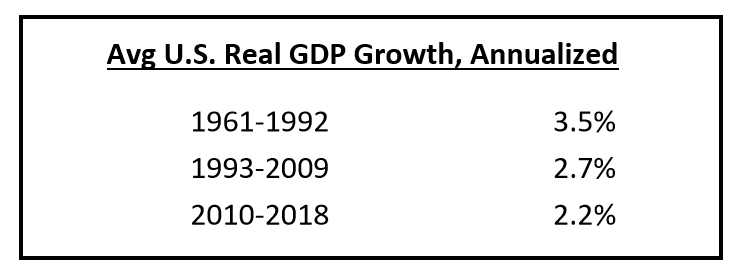

Consider this very basic mathematical story below. The populist angst that underlies these data points are hard to deny. Government spending has massively increased in that last decade. The result has not been enhanced GDP growth (as Keynes would have told us to expect), but the worst GDP growth since the Depression. Government deficits have exploded. Bond yields are by far the lowest for the last 10 years that they have been over the last 60 years. And yet, look at economic growth …

Government spending crowds out the private sector, period. This is the economic reality neither party has any interest in addressing, and it is imperative that investors understand it.

Politics & Money: Beltway Bulls and Bears

- From a market standpoint, the largest “political” event of the week was likely Peter Thiel’s speech accusing a large Silicon Valley search engine of potentially being in bed with the Chinese government, and declarations from the president afterward that he wanted to look into it further. European Union investigations into the largest e-commerce company in the world also surfaced. The political wars on big tech continue, and it does not appear they are anywhere near the finish line.

- I kid you not that I have lost track of how many times the media has hyped up a debt ceiling/budget impasse, and it has flopped as any kind of real news or market story whatsoever. A budget deal right now before the August recess looks tricky but monitoring the day-by-day details with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin is rather tedious. While many praise the idea of bipartisanship, I actually am sad to say that the two sides have very little daylight between them here (meaning, neither side is worried about how much is being spent, so why should they not come to a deal?). I am not sad about a deal getting done; I am sad that the reason why is that no one cares about excessive spending. No one.

- A price-fixing deal in pharma is another example of undesirable bipartisanship. It may be the negotiating tool used to get the new NAFTA across the finish line, which I admit would be a dual political victory for the Trump administration, but price control mechanisms in the hands of government have not often proven to be good, for customers, patients, producers or investors.

Chart(s) of the Week

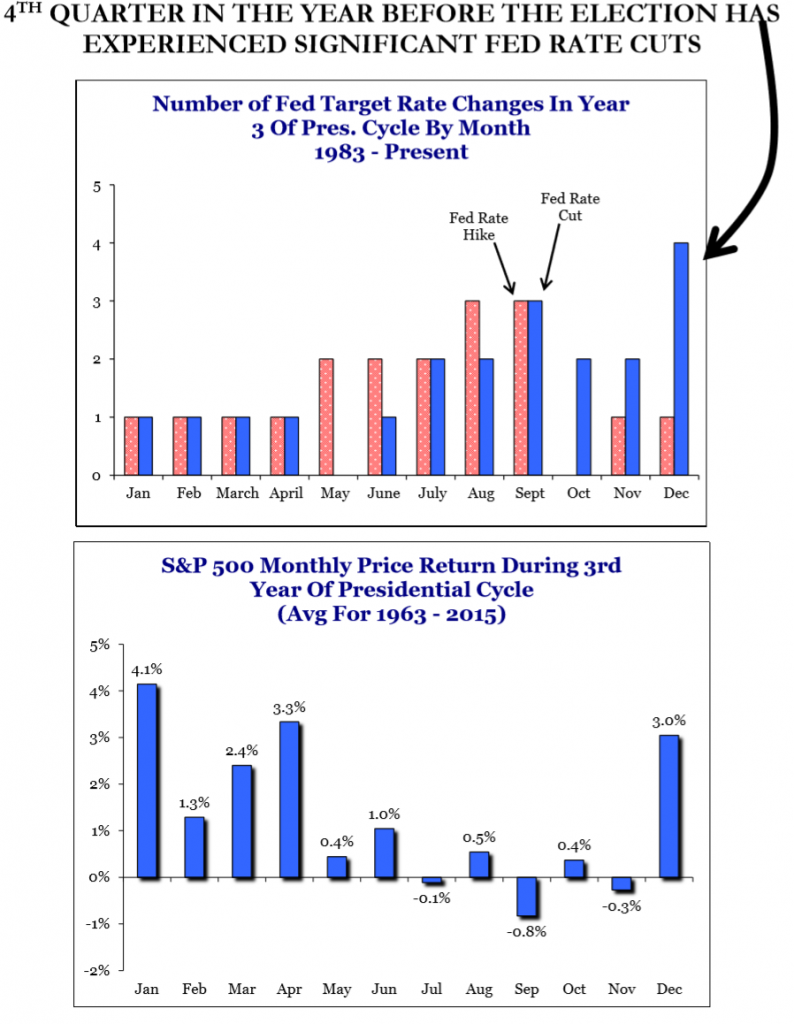

This week you get a two-for-one Chart of the Week, with the top chart showing the history of Fed rate cuts in year three of a Presidential term. Since 1983 there have been eight rate cuts but just two rate hikes in the fourth quarter of such years. The chart below that shows the history of calendar month returns in the stock market in year three of presidential terms.

Now, before you actually look at the charts, do I believe that past is prologue when it comes to calendar incidents? Not even a little bit. At best, these charts just capture a variety of events over the years and “average” them together … The history is interesting, and the averages may be noteworthy, as long as no one pretends they have predictive value. The lack of equivalence between correlation and causation does not mean we should not look at correlated events and wonder what caused them.

* Strategas Research, Policy Outlook, July 15, 2019, p. 2

Quote of the Week

“Only the paranoid survive.”

— Andy Grove

* * *

Thank you for making it to the end of the Dividend Cafe (assuming you didn’t skip ahead to the end). This was definitely a week where I could have gone on and on had I not cut myself off. Please do reach out with any questions about your portfolio, your positioning, and where our perspective on markets and the economy is being applied to your specific financial goals. That is, always and forever, what it is all about — applying the financial markets to the specific goals of actual people.

To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

This week’s Dividend Café features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet

The Bahnsen Group is a team of investment professionals registered with HighTower Securities, LLC, member FINRA, SIPC & HighTower Advisors, LLC a registered investment advisor with the SEC. All securities are offered through HighTower Securities, LLC and advisory services are offered through HighTower Advisors, LLC.

This is not an offer to buy or sell securities. No investment process is free of risk and there is no guarantee that the investment process described herein will be profitable. Investors may lose all of their investments. Past performance is not indicative of current or future performance and is not a guarantee.

This document was created for informational purposes only; the opinions expressed are solely those of the author, and do not represent those of MoneyandMarkets.com, HighTower Advisors, LLC, or any of its affiliates.