A recent report by the Mises Institute says more than half of Americans get more money in welfare through things like Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps and Social Security than they pay in taxes each year. Another report by the Congressional Budget Office earlier this year shows that only the top two income quintiles in the U.S. pay more in taxes than they receive in government transfers.

Per Mises Institute:

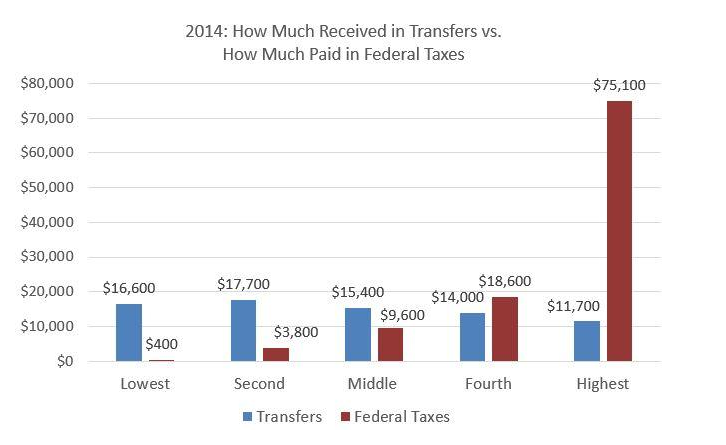

Not surprisingly, the three lowest income quintiles receive far more in transfers than they pay in taxes:

In the lowest quintile, households pay only $400 in taxes (as of 2014, the most recent data available) while receiving more than $16,000 in various types of tax-funded transfer payments.

The end result is households in the bottom three quintiles have higher incomes after taxes and government transfers than they do before taxes and transfers:

The second-to-top quintile is slightly worse off after taxes and transfers, and the highest quintile is sizably worse off. In other words, the top two income quintiles are subsidizing the bottom three, and the advantage, proportionally speaking, gets larger as income goes down.

The Politics of a Majority on the Dole

The article notes as Ludwig von Mises once said, once the majority of a voting population takes in more benefits than it pays out in taxes, voters will demand even more wealth from government programs. The political implications are dire because then a minority of the population will have to subsidize the majority. Market economics in turn become less popular because voters realize that instead of working for a living, they can vote for a living.

These findings don’t always apply at the level of the individual household, of course. In the middle quintile, especially, we’ll find some households that are indeed worse off after taxes and transfers than before. This will especially be the case for households that do not yet receive old-age benefits such as Medicare and Social Security. Those households are currently being taxed to pay for current recipients of SS and Medicare. Later, however, those households will begin to receive those benefits. And, over a lifetime, they’re likely to receive more in benefits than what they “paid in.”2 This notion of “paying in,” however, is pure fiction, and there is no “trust fund” for old-age benefits, and all benefits received at any given time are funded via taxation of current wage earners.

This again has huge implications because voters receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits know any cuts in government spending will likely affect their checks.

This is why neither major party ever seriously talks about cutting Medicare or Social Security, and why Donald Trump has even recently declared his own love for Medicare. It’s simply a redistribution of income and wealth from current wage earners to current recipients, and for most elected officials, attempting to cut these benefits would be political suicide.

At the low end, benefits more frequently take the form of “means-tested” benefits such as Medicaid and food stamps. And since these benefits are geared toward low-income earners, we naturally see more benefits going toward the lowest earners. Indeed, in the lowest quintile, market income is less than half of income after taxes and transfers.

But for many voters, the reality is this: any significant cuts in federal spending will mean less government benefits, either now or later.

Since so many households at the lowest end to the middle of the spectrum get more in benefits than they pay out, those voters then think tax cuts don’t benefit them while spending cuts absolutely affect them.

So there is a lot of pressure to maintain current spending levels or even increase them, while tax cuts aren’t nearly as popular.

Ultimately, perceptions matter and the CBO report shows that many voters receive government-subsidized checks of all kinds, and the perception is that cuts in spending will cost those who have become accustomed to taxpayer-funded benefits. And those effects on voting patterns and public policy are very real.