British euroskeptic politician Nigel Farage tried to ramp up the pressure on Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson on Friday, saying his Brexit Party will run against the Conservatives across the country in next month’s election unless Johnson abandons his divorce deal with the European Union.

Farage’s party, which was founded earlier this year to push for no-deal departure from the EU, has seats in the European Parliament but none in Britain’s Parliament. It rejects Johnson’s divorce deal, preferring to leave the bloc with no agreement on future relations in what it calls a “clean-break” Brexit.

Launching the Brexit Party’s campaign for the Dec. 12 election, Farage said Friday that Johnson’s deal “is not Brexit” because it would mean continuing to follow some EU rules and holding years of negotiations on future relations.

“Boris tell us this is a great new deal. It is not. It is a bad old treaty and simply it is not Brexit,” Farage said.

He spoke a day after U.S. President Donald Trump barged into the British election campaign, urging his friend Farage to make an electoral pact with Johnson’s Conservatives. Trump told Farage on the politician’s radio phone-in show Thursday that he and Johnson would be “an unstoppable force.”

Trump also undermined Johnson by claiming that “certain aspects” of the prime minister’s EU divorce agreement would make it impossible for Britain to do a trade deal with the U.S.

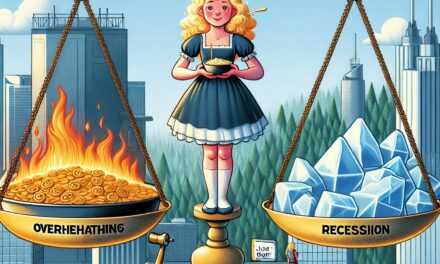

The ability to strike new trade agreements around the world is seen by Brexit supporters as one of the key advantages of leaving the EU. Most economists, though, say trade deals with the U.S. and other countries are unlikely to compensate for Britain’s reduced commerce with the EU, which currently accounts for half of U.K. trade.

Forecasters say a no-deal Brexit would have a more severe effect on the U.K. economy and would hurt EU nations as well.

Farage, who played a key role in the 2016 campaign for Britain to leave the EU, said that if Johnson agreed to abandon his deal, the Brexit Party would form a “non-aggression pact” with the Conservatives, standing aside from running against them in many areas.

All 650 seats in the House of Commons will be up for grabs in the election that is coming more than two years early, with winners to be chosen by Britain’s 46 million voters.

If the Brexit Party runs in only a small number of seats, that would help the Conservatives, who are vying with Farage for the support of Brexit-backing voters.

“I believe the only way to solve this is to build a ‘leave’ alliance across this country,” Farage said. “If it was done, Boris Johnson would win a very big majority.”

Farage warned that if Johnson rejects the offer, “we will contest every single seat in England, Scotland and Wales.”

Farage said Johnson needed to make up his mind before the nominations for election candidates close on Nov. 14.

Johnson, however, has already ruled out an electoral pact with Farage.

“We are not interested in doing any pacts with the Brexit Party or indeed with anybody else,” Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick said Friday. “We are in this to win it.”

The prime minister sought this election to break the political impasse over Britain’s stalled departure from the EU.

Johnson had promised for months that the U.K. would leave the 28-nation bloc on the scheduled date of Oct. 31, “come what may.” He struck a divorce deal with the bloc last month, but Parliament blocked his plan to rush it into law in a matter of days.

Last week the EU granted Britain a three-month Brexit delay, setting a new Jan. 31 deadline.

Johnson blames the opposition for the failure to leave the EU on Thursday.

While the Conservatives have a wide lead in most opinion polls, analysts say the election is unpredictable because Brexit cuts across traditional party loyalties.

The Brexit Party also poses a threat to the main opposition Labour Party in traditionally Labour-supporting post-industrial areas of Wales and northern England, which voted in 2016 to leave the EU.

On the other side of the divide, the centrist Liberal Democrats, who want to cancel Brexit, are wooing pro-EU supporters from both the Conservatives and Labour in Britain’s big cities and liberal university towns, which largely voted to stay in the EU in 2016.

Left-of center Labour, which has its own internal divisions over Brexit, is trying to shift the election battleground from Brexit onto more comfortable domestic terrain: the rising inequities in Britain. Labour is hoping that voters want to talk about health care, the environment and social welfare — all of which saw years of funding cuts under Conservative governments — instead of holding more debates on the seemingly endless topic of Brexit.

© The Associated Press. All rights reserved.