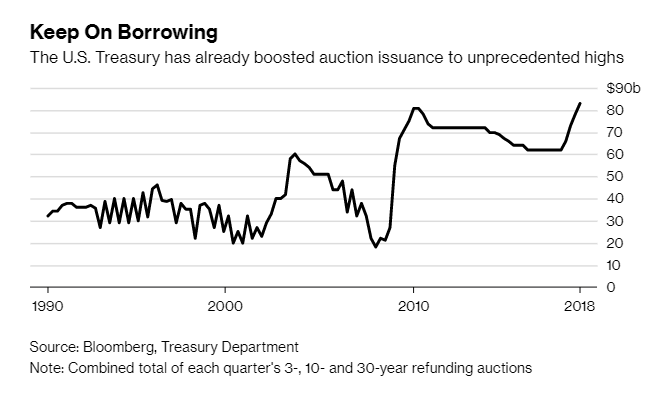

For the second straight year, the U.S. Treasury is set to finance the ballooning national deficit by selling about $1 trillion worth of long-term debt, a move that DoubleLine Capital LP’s Jeffery Gundlach says will sink the economy under “an ocean of debt.”

Per Bloomberg:

Many strategists at primary-dealer firms predict that this Wednesday’s quarterly refunding announcement will see the Treasury maintain note and bond sales at the record high levels they have boosted them to in recent months.

The total amount of 3-, 10- and 30-year securities to be offered at next week’s refunding auctions is seen by most at $84 billion. While that’s $1 billion more than the total for these maturities three months ago, that’s only because the size of the three-year sale was already nudged higher in December.

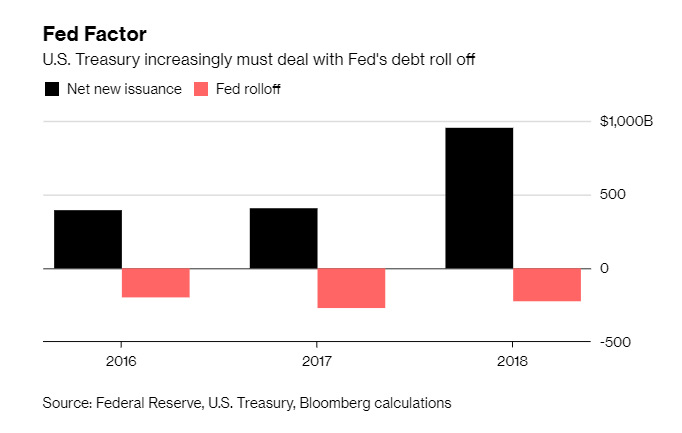

A heightened supply of Treasury securities follows tax cuts and government spending increases implemented under the current administration. That’s darkening a fiscal outlook already made worrisome by rising entitlement-program expenses and higher costs to service America’s nearly $16 trillion in debt. The Federal Reserve’s balance-sheet runoff is also adding to supply, forcing Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to tap the public for more funding.

“We’ve seen deficits continue to blow out,” said Brian Edmonds, head of interest-rates trading at Cantor Fitzgerald in New York. “We are going to see more and more supply.”

Cantor, along with dealers including Citigroup Inc., TD Securities, Deutsche Bank AG and Wells Fargo Securities, sees the Treasury keeping auction sizes unchanged for nominal coupon-bearing debt.

A few dealers, including NatWest Markets and UBS Securities Inc., expect the Treasury to notch coupon-bearing debt sales slightly higher again. Among these outliers are strategists at UBS Securities Inc. who predict the 3-, 10-, and 30-year refunding issues will each be increased by $1 billion over the coming three-month period.

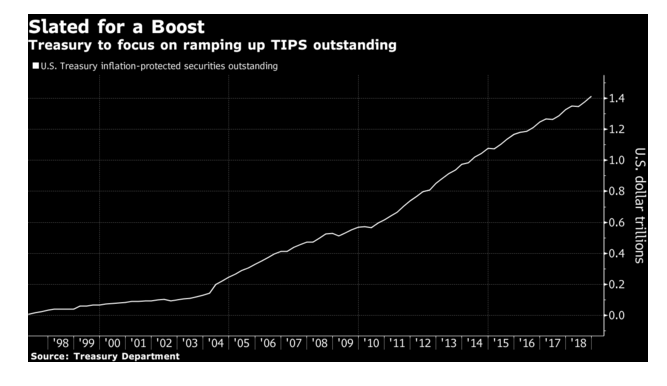

After focusing last year on increasing nominal debt, prior guidance from the Treasury has dealers saying more detail is likely in the coming months on plans to boost auction sizes for Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities, or TIPS. That’s on top of the new five-year October TIPS that’s already been slated for the calendar.

Such changes may result in additional net TIPS issuance of $26 billion this year, according to a note from Zachary Griffiths, a strategist at Wells Fargo Securities.

The Treasury’s total net new issuance in 2018 amounted to $1.34 trillion, more than double the 2017 level of about $550 billion. In 2019, it will be $1.4 trillion, with $1.11 trillion from more coupon-bearing debt and the rest in bills, according to forecasts from Steven Zeng of Deutsche Bank. Annual new issuance will range from $1.25 trillion to $1.4 trillion over the next four years, he says.

The fiscal 2018 U.S. budget gap hit a six-year high of about $780 billion, and the Congressional Budget Office forecasts it will reach $973 billion in 2019 and top $1 trillion the next year. Over the next decade, the U.S. government will spend about $7 trillion just to service the nation’s debt, according to the CBO.

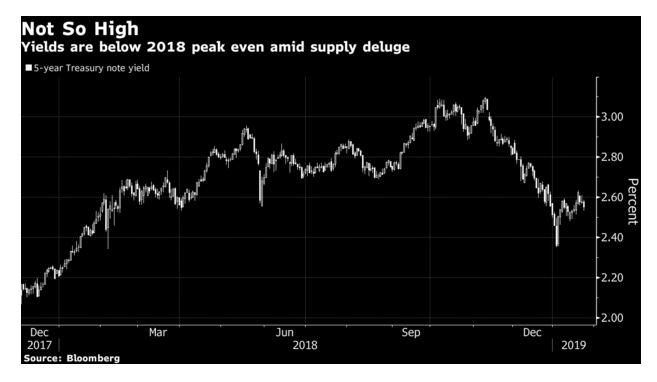

Despite the flood of supply, Treasury yields haven’t surged higher because demand hasn’t slackened for the world’s safest securities, which also act as a global benchmark. Yields on the five-year note, a tenor closely in line with the average maturity of U.S. debt at 69 months, has risen about 0.4 percentage point since 2017 and was about 2.60 percent on Monday. It’s down from a peak last year of 3.10 percent.

“With all these problems, we’re still in better shape than so many of the other advanced economies,” said Phillip Swagel, a University of Maryland professor and former Treasury official during the George W. Bush administration.

Investors aren’t so sanguine.

Last year the Treasury also had to deal with a central bank that sped up the amount of debt it allowed to mature and roll off its balance sheet. The Fed’s Treasury holdings fell by about $230 billion in 2018, compared with a reduction of $18 billion in 2017. About $271 billion should roll off this year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Last year the Treasury also had to deal with a central bank that sped up the amount of debt it allowed to mature and roll off its balance sheet. The Fed’s Treasury holdings fell by about $230 billion in 2018, compared with a reduction of $18 billion in 2017. About $271 billion should roll off this year, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.

“Net borrowing needs will continue to increase due to the expected increase in the deficit combined with funding needs coming from the Fed’s debt run off,” said Margaret Kerins, global head of fixed-income strategy at BMO Capital Markets Corp. “Given the global backdrop with Brexit and China’s economy slowing down, there is really a bid for safety, liquidity and quality — which means Treasuries — and that’s keeping yields in check to some degree.”