The bond market was acting as a safe haven once again Wednesday, as investors fled the tanking stock market and sent bond yields to lows that haven’t been seen in years.

The yield on the 10-year Treasury note fell to as low as 1.59% during the stock market exodus, and the 30-year Treasury bond fell to 2.12%. Both yields have not touched that level since fall in 2016, according to CNBC. The 10-year yield recovered a bit of the drop, and was sitting at 1.66% around 1:35 p.m. EDT. By market close at 4 p.m. EDT the 10-year yield was back to 1.71%.

But it’s pretty shocking how quickly bonds have reached this level. The 10-year note has dropped 40 basis points in the last month, with 35 points of that drop coming in August, according to CNBC. The yield finished off July above 2%.

Investors weren’t only fleeing the U.S. market, though, as rates in the United Kingdom and Germany also hit record lows Wednesday. Germany’s 10-year bund dropped to -0.6%, and its 30-year bund hit -0.137%, both records, according to CNBC. U.K. 10-year and 30-year yields also dropped to new lows.

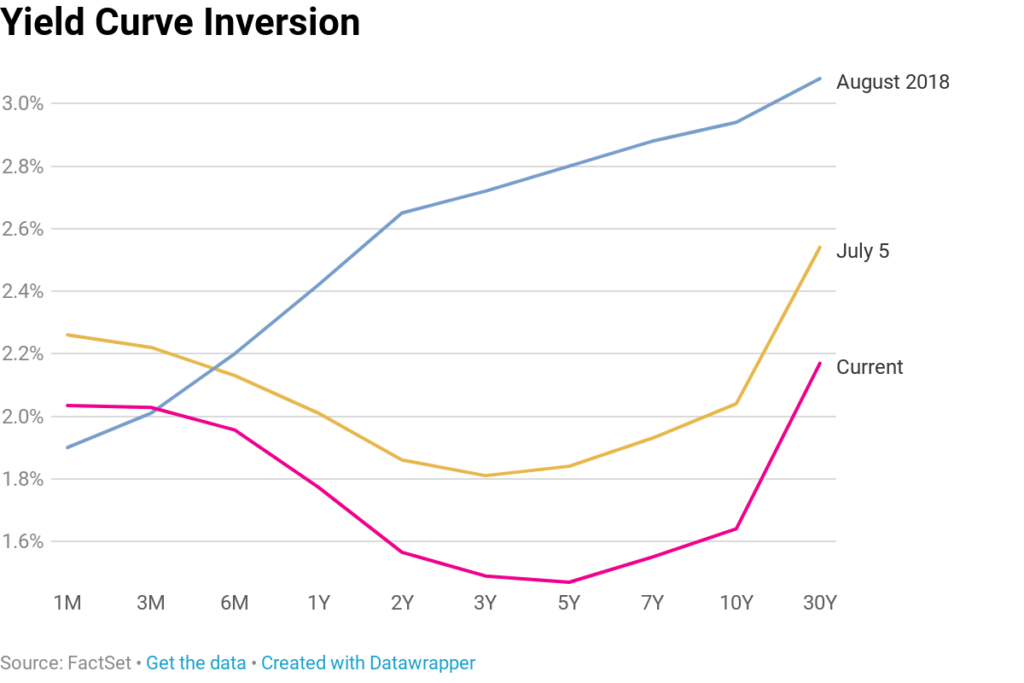

Bonds dropping also leads to greater flattening and inversion of the yield curve, a recession indicator. The spread between the 2-year Treasury yield and the 10-year yield hit a low of 7.4 basis points. That’s the lowest level seen since June of 2007, or right before the financial crisis.

“The flattening in 2s/10s should be expected in a world of rising global macro risk, coupled with falling forward inflation expectations,” Jon Hill, rates strategist at BMO Capital Markets, said in an email to CNBC. “There is an element of fear here that the Fed won’t cut as much as necessary to keep the cycle going and maintain inflation near 2%. This keeps front-end rates elevated while long-tenor yields fall.”

“However, we think eventually this gives way to a more aggressive Fed cutting campaign — even a ‘mid-cycle’ move could easily be in the 100 bp to 125 bp magnitude,” Hill added.

So what’s driving this exodus? Many investors fear there is no end in sight to the prolonged trade war between the U.S. and China. In response to stalled negotiations last week, Trump announced another round of tariffs on $300 billion of Chinese imports set to begin on Sept. 1. China responded by cutting off purchases of U.S. agricultural goods and weakening their currency against the dollar, prompting fears of a currency war between the world’s two largest economies.

Lower rates also are driving investors to bonds, and some other global economies joined the U.S. Federal Reserve in cutting interest rates in order to stimulate the economy.

“Overnight many central banks cut rates, including New Zealand and this is dragging all yields lower,” Jim Caron, managing director of global fixed income at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, told CNBC. “The Fed is lagging this cycle, so it is no surprise” to see the yield curve continue to invert.

The Fed’s decision in July to only cut by 25 basis points “was a policy mistake and they should have gone 50 bps,” he added. “The largest central bank in the world, the Fed, needs to lead not follow. It is important they get out ahead of the risks associated with a trade war.”