I received a question from one of my subscribers, Robert B. He writes:

Since we don’t lose money on a stock until we sell it, why are we selling stocks? If a stock was a good investment before COVID-19, why won’t it be a good investment after outbreak is gone?

That’s an excellent question, Robert. It really boils down to your investment time frame, your stomach for risk and your appetite for gains.

In fact, economist John Maynard Keynes has three interesting quotes I think sum up this pretty well.

Keynes Quote No. 1: “In the Long Run, We’re All Dead”

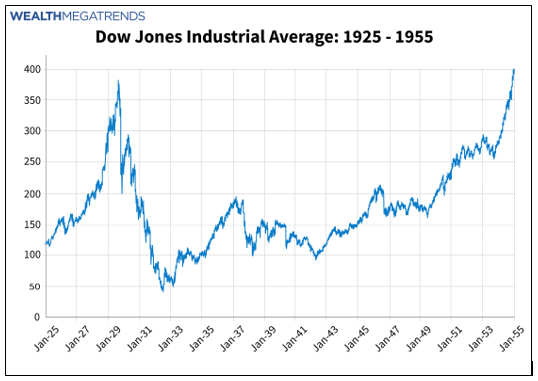

You probably know I’m something of an amateur historian. Here’s a fun fact: Back when there were the old silverbacks on Wall Street who actually lived through the 1929 crash, they’d tell you it took 25 years for the markets to recover.

And historical charts of the Dow back them up.

Looking at this chart, you can see the recovery was a long one. Accounting for dividends, the actual timeframe was a little smaller. But let’s go by price action for now.

After the initial crash of 1929, there was a rebound and the market made back 50% of its losses. Then it keeled over and bounced its way down, down, down. The 1932 plunge was so big it made the crash of 1929 seem small. There was 50% depreciation even from the lowest point of 1929.

Finally, we got to a gradual but slow improvement.

People blamed many things for the crash of ’29, including overvalued stocks and a feckless federal government. Not that we have those things nowadays (whistles nervously).

But besides those, I can tell you that little-understood economic and market cycles had a lot to do with it. At Weiss, we follow the same cycles that not only showed the rally back in the late 1920s was likely, but also that the big crash following it was also predictable.

What can we learn from this? First, let’s remember economist John Maynard Keynes’s famous reply to someone who told him a certain investment would go up in the long run. “In the long run,” Keynes said, “we’re all dead.”

I should mention that the worst stocks in the Dow went bankrupt and were replaced by other companies. If you held those failing stocks, you’d have held them all the way to zero.

But it’s also true that an index hides the outperformance of individual stocks. For example, Dow Chemical recovered to its break-even point by 1933. Honeywell (HON) and 3M (MMM) recovered by 1936.

Now, when stocks crash, should you hold what you have or cut your losses and get out? Or should you look for stocks that will go up?

I’d say buy the things going up.

Keynes Quote No. 2: “The Market Can Remain Irrational Longer Than You Can Remain Solvent”

Anyway, perhaps you say: “Pshaw! Don’t bother me with your ancient history, old man! I only trust recent market action!”

Okay, is a comparison with the crash we saw during the Great Recession of 2008-2009 recent enough for you?

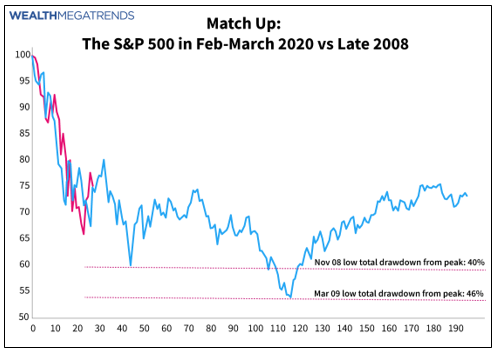

This chart matches up the price action in the S&P 500 of today (red line) to the S&P 500 in late 2008 into 2009 (the blue line).

Today, we’ve seen the government launch a huge relief program, which is either $2 trillion or $6 trillion, depending on if you include new Fed lending programs. The Great Recession was met with a money cannon, too — the government launched the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) that bailed out the banking and housing sectors in September 2008.

But in spite of TARP and stimulus measures, the S&P 500 fell 46% over the next 18 months. Combined with its losses in 2007-08, the index fell 57% from its 2007 high point to that March 2009 low.

From its peak in October 2007, the market didn’t make sustainable new highs until January 2013. That’s a long time. It takes a real spine of steel to ride that out. So, you have to ask yourself: What amount of risk can you tolerate?

That said, if you bought near the bottom? Oh, some of those returns were sweet. Believing in those long-term rewards and buying extreme lows is dependent on your appetite for gains. Does it outweigh your tolerance for risk?

So, here are four things to keep in mind about selling losing stocks …

First, if a stock falls hard, look at it and ask yourself: “Would I buy it now?” If the story has changed and you wouldn’t, maybe you should sell.

Second, a stop-loss order prevents emotions from taking over. In any reasonable timeframe, the odds are that stop-losses will limit YOUR losses.

You might THINK that a certain stock is irrationally valued by the market. But as Keynes also famously said, “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

Third, dividends COULD be a good reason to hold. If a company pays a dividend, regularly raises that dividend and seems immune to whatever is afflicting the market or broader economy, then it makes your recovery much more likely and much shorter.

For example, when you figure in dividends, the Dow recovered its 1929 losses in 14 years, not 25. But back then, dividends paid an average of 14%. That seems fantastical in today’s market.

And fourth, don’t let disappointment blind you to opportunities. Walking away from the market and burying your money in the back yard probably isn’t a good strategy.

Keynes Quote No. 3: “When my information changes, I alter my conclusions. What do you do, sir?”

Let me close with a final Keynes quote, the one above. My view is we are headed into the worst recession since World War II, and potentially a depression.

Our Federal government seems not only incompetent, but downright malevolent. We were saved in past crises by leaders who put America first. Now, they seem to only put the fat cats first.

So, I expect a bumpy ride lower, dotted by short, sharp bear-market rallies.

Weiss Cycle Research says I’m right. I would be happy for the optimists to be right, of course. And maybe they are. If that happens, I’ll change my mind.

But for now, it seems smart to let stop-losses work, raise cash and put that cash to work in investments that can outperform going forward.

All the best,

Sean