European Central Bank head Mario Draghi is credited with saving the euro by using new and sometimes unorthodox policy tools. The question now is, will the next ECB president be as quick to use them — or invent new ones — as Draghi has been?

European leaders are searching for a replacement for the 71-year-old Draghi, whose term expires Oct. 31. But whether candidates share his pragmatic and activist approach is not the only consideration: Picking the ECB president is also part of complex horse trading among governments over top EU jobs.

Their choice will determine whether the next ECB leader will be someone that is as quick to step up in a crisis, and as willing as Draghi was to innovate and resist criticism. European leaders meeting Thursday and Friday will discuss top European Union jobs, though they may not yet reach a deal on any of them.

Speculation so far has focused on Jens Weidmann, head of Germany’s Bundesbank national central bank and an opponent of some of Draghi’s new measures; Francois Villeroy de Galhau, the head of the Bank of France; former Finnish Central Bank head Erkki Liikanen, and current Finnish central banker Olli Rehn. Leaders will pick one for an eight-year, non-renewable term in a process that some think risks focusing more on national turf wars than on the policies the candidate would pursue.

In Weidmann’s favor is the fact that Germany has never held the ECB presidency since the euro was launched in 1999. He is a stimulus skeptic, however, and may face opposition from indebted countries such as Italy that have benefited from Draghi’s stimulus. All the candidates have served under Draghi on the ECB’s rate-setting council through their posts as heads of national central banks.

Some ECB watchers are disconcerted that the job is being seen as secondary to choosing successors for Jean-Claude Juncker, the head of the EU’s executive arm, the European Commission, and for Donald Tusk, president of the European Council of heads of state and government. The thinking goes that Germany and France cannot hold both the commission and the ECB job; that means that if a German such as European parliament member Manfred Weber is chosen for the commission, Weidman’s chances at the ECB would suffer and Villeroy de Galhau’s would improve — and vice versa in case of a French commission president.

Yet it was the ECB that stepped up during the debt crisis and took quick action credited by many with keeping the euro from breaking up. Draghi’s willingness to act was crucial during market turmoil that hit the eurozone in 2011-2012, says Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg bank in London.

“Draghi has steered the eurozone through a tremendously difficult time, through a much bigger storm than anyone could have imagined,” Schmieding said. “He made sure that the ECB rose to the unforeseen challenge, in my view without breaking or violating the mandate, but under unforeseen circumstances he found new tools to help the ECB meet its mandate.”

Draghi’s trademark moment came on July 26, 2012, as Italy, the third largest country in the euro, was facing unsustainably high borrowing costs that threatened its financial stability. Draghi said that “within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

The utterance proved to be a turning point for Europe.

The ECB followed up with a plan to purchase the government bonds of countries experiencing borrowing costs that were out of line with the ECB’s efforts to steer interest rates in the eurozone. Market panic around Italy subsided. The program survived court challenges from opponents who said the ECB exceeded its powers.

As the eurozone slowly recovered, Draghi and the bank’s governing council backed other innovations to push up alarmingly weak inflation that threatened the eurozone with crippling deflation. Under Draghi, the bank used the unorthodox tool of negative interest rates, putting a minus 0.4% rate on deposits left at the central bank by commercial banks, a penalty to push them to lend. Lastly, the bank bought 2.6 trillion euros ($2.9 trillion) in government and corporate bonds across the eurozone over almost four years, a move that pumps newly created money into the banks with the aim of supporting lending and a healthier level of inflation.

Those tools remain for Draghi’s successor. The program that halted the crisis in Italy was opposed, however, by Weidmann. He has argued that buying bonds takes the heat off governments to shape up, and that it could unfairly spread losses to other countries in case a country defaults on bonds held by the ECB. He softened his position in an interview with the Die Zeit weekly published Wednesday, saying he recognized the bond purchase offer as legal and binding — a statement that appeared aimed at reassuring countries worried he would reverse it if chosen. Villeroy de Galhau has expressed concern that the negative interest rate could hurt bank profits; Rehn has proposed a top to bottom review of the ECB’s monetary policy.

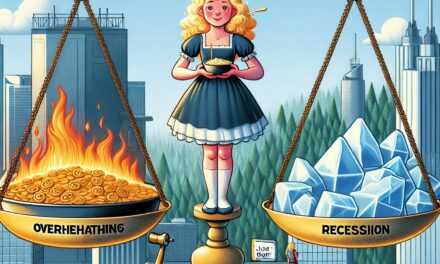

That is because despite all the stimulus, inflation at 1.2% remains stubbornly below the ECB’s goal of just under 2%. How to finally achieve the goal will be a key problem for Draghi’s successor.

Carsten Brzeski, chief economist for Germany and Austria at ING, said that no future ECB president could afford to ignore the bank’s firefighting role in any new crisis, and suggested that Weidmann could prove “much less dogmatic” as the head of the ECB, a role that requires building consensus on the 25-member rate-setting board.

“We could see a subtle, gradual change in how the ECB will reach to developments,” said Brzeski, with the bank more likely to take a wait and see approach before acting.

© The Associated Press. All rights reserved.