Fed Chair Jerome Powell gave a recent speech where he decried Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), and Wall Street generally agrees that a free-spending government unconcerned about national debt is a recipe for disaster.

“It’s been a race to the bottom by all central banks. Everyone printed all this money.’’

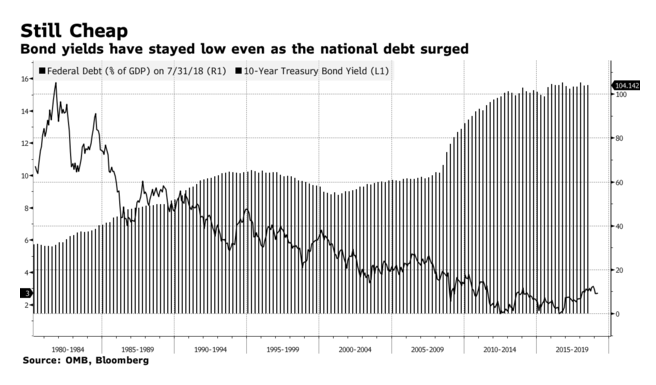

But the market also is surprisingly comfortable with the growing national debt, which ticked above $22 trillion for the first time last month.

Per Bloomberg:

Benchmark 10-year yields remain below 3 percent, a historically low level, even as America plunges deeper into deficit and jacks up debt sales to a record. That’s no surprise to MMT economists — who predict more of the same. They argue that because the U.S. borrows in its own currency, it can print dollars to cover its obligations, and can’t go broke. And when inflation is low, as it is now, there’s room to spend more.

Last week, Federal Reserve Chair Powell described that school of thought as “wrong.’’ Investors tend to agree that it would end in tears one day. Just not anytime soon.

“You have to say that markets are willing to be patient for a while with this kind of stuff,’’ said Michael Shaoul, chief executive officer at Marketfield Asset Management LLC.

Everyone Did It

One precedent is the trillions in debt that the Fed purchased after the 2008 financial crisis. The giant experiment in cheap money didn’t trigger inflation or awaken the bond vigilantes. Instead it has helped keep yields down.

There were no adverse consequences for the U.S. because everyone else was doing the same thing, according to Mark MacQueen, co-founder of Sage Advisory Services, which manages about $13 billion. “It’s been a race to the bottom by all central banks,’’ he said. “Everyone printed all this money.’’

Now, the Trump administration is engaged in a fiscal experiment to match that monetary one, pumping deficits into an expanding economy on a scale America hasn’t seen since the 1960s. The stimulus has contributed to faster growth. And the prospect of retrenchment under a Democratic successor is fading.

The bond vigilantes, who famously compelled President Bill Clinton to scale back his first term agenda and focus on deficit reduction instead, don’t bother Democrats like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. The New York congresswoman is proposing a 70 percent tax rate for the rich, but that would only recoup a fraction of the costs of a Green New Deal or Medicare For All — programs endorsed by Ocasio-Cortez and several of her party’s 2020 frontrunners. She’s invoked MMT as a way to pay for the rest.

‘My Market Hat’

Shaoul is skeptical partly because he says experience shows that government isn’t good at allocating resources: “I think MMT is a terrible idea — as a taxpayer.’’ His take as an investor is a bit different.

“If I put my market hat on,’’ he said, “you could probably get away with a further loosening of fiscal controls, and a central bank supporting it.’’

Whether Fed backing would be forthcoming is an open question. Powell was asked about that last week. “Our role is not to support particular policies,’’ he replied. The Fed, which again came under attack by Trump this past weekend for keeping policy too tight, is currently offloading bonds — one reason why the Treasury has to sell so many.

But Shaoul says the broad trend since 2008 is toward coordination of monetary and fiscal policy. “What I did understand 10 years ago was that this was a really big change,” he said. “Money, public finances and central banks were going to be working with one another.’’

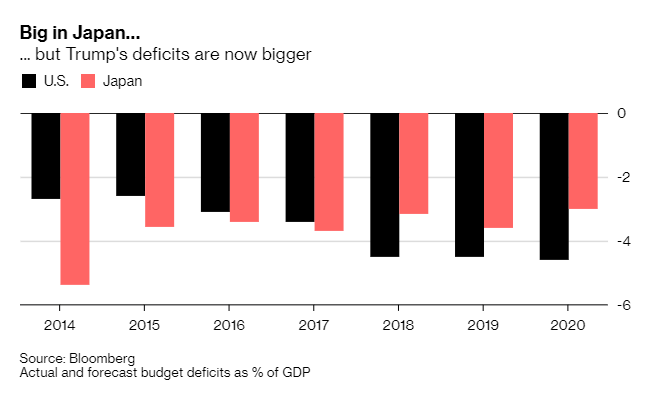

That was quickly evident in the U.S., with the Fed’s Ben Bernanke and Treasury’s Hank Paulson forming a crisis tag-team. It’s been taken even further in Japan, where private credit collapsed more than a decade earlier. Since then Japan has run up a public debt, financed with the help of its central bank, that dwarfs America’s. Yet it has little inflation and can borrow money virtually for free.

Bill Gross says he admires what Japan has done to revive its economy. The former bond king, once among the most vocal critics of post-crisis stimulus, now sounds like a near-convert to MMT when he suggests the U.S. government could double its deficit.

Donald Trump hasn’t gone that far. Still, the president — who inherited an already widening budget gap — has widened it some more. The shortfall reached $779 billion in his first full fiscal year in office. It’s now bigger (as a share of the economy) than Japan’s, and on track to exceed $1 trillion in 2022. Outlays on health care, social security and debt servicing are rising, while Trump’s tax cuts subtracted revenue.

With Treasury yields low, the deficit “may look like it is a free lunch,” Deutsche Bank’s chief international economist, Torsten Slok, wrote last week in response to what he said was a “steady stream” of client questions about MMT. He warned that the impact may show up elsewhere, as the growing supply of risk-free government assets sucks money out of other credit and even equity markets.

“I know the deficit continues to be absorbed by the bond market’’ said Gary Pollack, head of the private clients fixed-income desk at Deutsche’s wealth management arm. Eventually, “it will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.”

MacQueen, at Sage Advisory, mostly shares that long-run pessimism. But he’s been working in financial markets since 1981, and well remembers Treasury yields close to 16 percent back then. He acknowledges that anyone wanting to try out MMT-type policies in the U.S. would likely find there’s some room to run.

“We’ll take the pain eventually,’’ he said. For now, “we’ve gotten away with it. And things look pretty good in the market.’’