The prospect of a government shutdown has Wall Street veterans sounding the alarm over another likely fight as reinstatement of the debt ceiling looms in March.

The near-complete inability for anyone in Washington to come to a compromise is renewing fears that the Treasury will need to resort to extraordinary measures to pay America’s obligations, according to a recent article by Bloomberg.

Congress has never failed to reach an agreement on the debt ceiling, but Wall Street experts are growing more and more concerned that a 2019 clash could be the worst yet, leading to a major disruption of the stock market.

“This shutdown episode is important because it’s a window into the governing dynamics next year, which is concerning because the debt limit comes back into play,” said Isaac Boltansky, a senior policy analyst at investment advisory firm Compass Point. “Legislative brinkmanship takes on a whole new market dynamic when it encompasses the debt ceiling. We are going to have a concentration of political risks that investors need to be aware of.”

Budget Battle

The government is just hours away from a partial shutdown with Congress at an impasse over funding President Donald Trump’s border wall. Republicans in the House on Thursday night sought to meet Trump’s demands, adding $5 billion for border wall construction to the Senate’s version of a stopgap spending measure, but Senators from both parties have indicated that the modified legislation won’t pass when the chamber returns for another vote on Friday. Trump on Friday warned that a shutdown “will last for a very long time” if Democrats vote against funding for the wall.

Nine of 15 government departments would shut down after Friday without a resolution. Stocks finally took note Thursday, extending their recent rout , and U.S. equity futures were lower on Friday.

While the economic impact of a shutdown would likely be limited, the consequences of similar strife over increasing America’s borrowing capacity could be huge, if recent history is any guide.

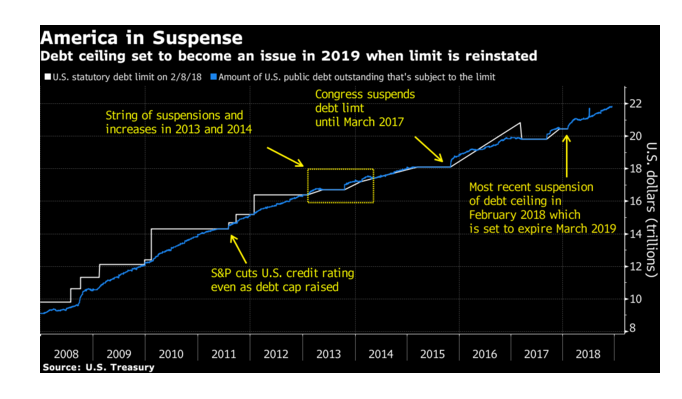

In 2011, a split House and Senate, similar to the incoming Congress, took the debt-limit debate down to the wire, prompting S&P Global Ratings to cutAmerica’s sovereign credit grade for the first time.

Ten-year Treasury yields slid from more than 3 percent to a then-record low of about 2 percent in the weeks surrounding the Aug. 2 drop-dead date as investors — somewhat counterintuitively — sought shelter in government bonds. The S&P 500 fell about 20 percent amid the turmoil, while the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index surged in the aftermath of the downgrade.

While longer-term Treasuries gained, some bills and short-tenor notes tumbled as traders avoided securities at risk of non-payment, leaving taxpayers on the hook for an addition $1.3 billion in interest payments for the fiscal year, according to the Government Accountability Office. Similar disruptions in the front end also occurred in the run-up to the 2013 and 2017 debt-ceiling deadlines.

“Given the political setup, unlike when we had a Republican Congress, we have increased risk around the possibility of going beyond the debt-limit suspension deadline, and Treasury having to use extraordinary measures,” said William Foster, a senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service, referring to accounting measures the Treasury uses to temporarily free up funds and remain under the statutory limit. “That’s what we are focused on, past the temporary shutdown, is the material risk around the debt limit.”

Market Mayhem

Should a similar scenario play out in 2019, however, some strategists see any market shakeup unfolding differently.

The dollar, which has gained almost 4 percent this year, and Treasuries, which have rallied in recent weeks amid signs the Federal Reserve is set to slow the pace of interest-rate hikes, are unlikely to act as havens as they did in 2011, given improved economic conditions elsewhere, according to Bank of America Corp.’s David Woo.

“The markets had to literally instill fear in politicians,” said Woo, the bank’s head of global rates and foreign-exchange strategy. “The first six months of 2011 was the most volatility in foreign exchange and rates that I remember in the last 10 years. Given we potentially go into a turmoil situation, there is clear downside risk to the dollar as, unlike before, people will look to other havens.”

The yen, at around 111 per greenback, will strengthen to 109 by June and 105 by December, Woo predicts, while the Swiss franc will also benefit.

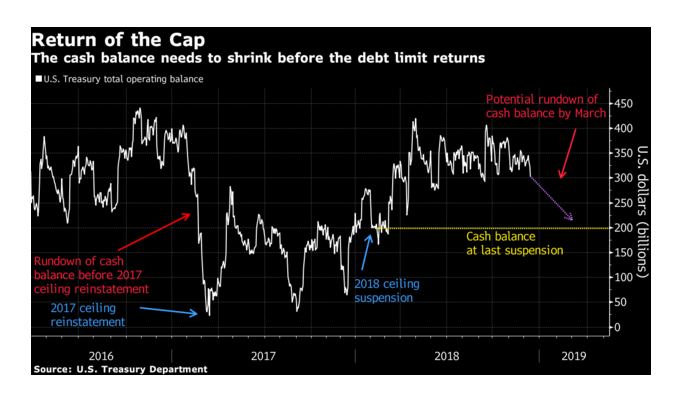

One silver lining this time around is that Treasury won’t have to whittle down its cash balance as much as in past episodes, a product of the size of its balance at the time the debt-ceiling moratorium was implemented.

The department will need to pay down about $120 billion of bills between now and the first half of February, according to Blake Gwinn, a strategist at NatWest Markets. Last year, the Treasury had to rapidly cut bill sales to reduce its cash balance from more than $400 billion to just $23 billion, fueling a spike in volatility in the normally sleepy market.

When exactly the Treasury’s extraordinary measures would run out still remains somewhat up in the air. The 2017 tax overhaul has made gauging the pace of revenue next year murky, according to Thomas Simons, an economist at Jefferies LLC. He expects a drop-dead date anywhere from mid-year to as late as the third quarter.

The other complicating factor, according to Simons, is that the incoming House leadership may start to turn their attention matters such as impeachment proceedings.

“The worry is that the debt limit is something that Congress lets slips through the cracks.”