The Good Thing About Value

Clint Eastwood must be a value investor. He understands that things can be good, bad and ugly.

I can’t think of a better description of value investing, a strategy that involves targeting companies with strong fundamentals and trading at a fair price.

Just like Clint, I’ll start with the good aspects of value investing. I’ll cover the bad and ugly later this week.

The good is what everyone knows about this strategy. It’s probably the most popular style of investing — at least when popularity is measured by how many people claim to invest this way.

Value investing has a long history. It dates back to at least 1934 when Ben Graham published his book, Security Analysis. Graham taught Warren Buffett decades after that and Buffett made his fortune using the principles Graham laid out.

And now the masses want to be like Buffett. That’s for good reason at first glance.

Long-term returns for the strategy are strong. According to one proponent of value:

Over the past 50 years, from 1968-2020, stocks in all three of Graham’s categories outperformed the S&P 500. Against an annual average rise in the market index of 10.3%, the bottom 20% by [price-to-earnings ratio] rose by 14.6%, the bottom 20% by [price-to-book value] by 13.9%, and the top 20% by dividend yield by 12.4%.

This sounds great.

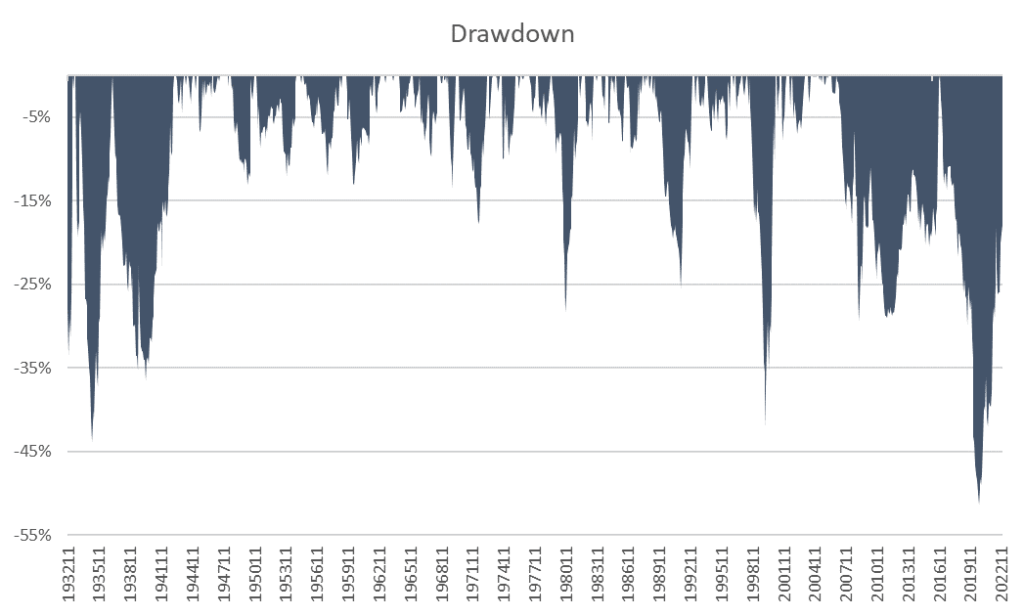

The chart below shows data for value from 1926 through 2007. The uptrend is interrupted by occasional downdrafts.

This chart ends in 2007. And I’ll tell you why below.

The Bad Thing About Value

Yesterday, I told you about how value investing delivers strong long-term returns — and that’s a good thing.

But today, I want to highlight the other side of the strategy. That’s the fact that there are large, long-term drawdowns associated with this investing style.

Tomorrow, I will look at the ugliest aspect of value investing, which is the reason I don’t think it’s the best approach for most investors.

Drawdowns are a euphemism for losses. It’s the amount your account loses, or draws down, from a high. And I believe it’s the most important measure of risk.

Drawdowns measure the percentage loss from an account high. We can easily convert this to dollars. A 50% drawdown in your $100,000 retirement nest egg is a loss of $50,000.

The reason I believe it’s the most important risk metric is because it allows you to see how much your life could change in a bear market. That 50% loss, no matter what your account balance is, would adversely impact your life if it occurs within a few years of retirement.

I’m using “adversely impact” as a euphemism for “devastate” since it sounds better. The truth is a large loss near retirement will change your life.

You may not retire on time.

You may not get a long-planned vacation.

You may not have money to help your children or grandchildren.

The risks are too high for me to consider. That’s why I look at drawdown. And the chart of value drawdowns is bad. You can see that, over the last three years, value investing experienced its worst loss since the 1930s.

This is based on data from Dr. Ken French. He co-authored many articles with Nobel Prize-winning economist Dr. Eugene Fama (you may recognize this name from my colleague Adam O’Dell’s own research).

It’s the longest and most accurate data available for analyzing value.

Since 2000, value has experienced frequent large drawdowns. You might have just half or three-quarters of the money you planned on for retirement if you stuck to value investing throughout that stretch.

While that’s bad, below, I’ll show why value is ugly.

The Ugly Thing About Value

Warren Buffett is revered by value investors. Many listen to the folksy wisdom of the Oracle of Omaha — and they like what they hear.

They know he has an extraordinary track record and strive to be like him.

So they try to be value investors.

Not me.

I understand something Buffett-wannabes don’t: I’m not him.

When Goldman Sachs needed $5 billion, they didn’t call me to offer 10% interest plus billions more in upside potential. They called Buffett, and he put the deal together in minutes.

Without his connections and experience, I can’t be Buffett.

Instead of trying to find nuggets of wisdom in Buffett’s words, I look to Clint Eastwood to understand investing styles. He tells us there is always the good, the bad and the ugly.

I’ve shared the good and the bad with you earlier this week. Now, to the ugly…

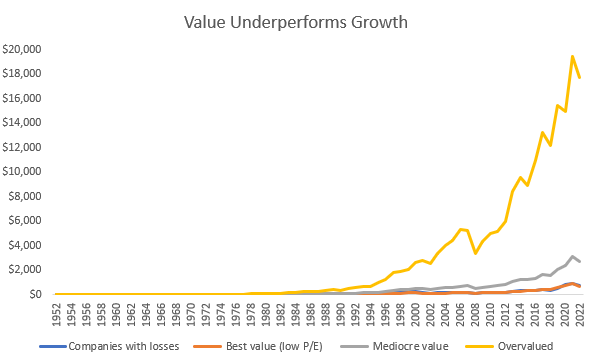

It boils down to this: Value underperforms growth investing most of the time. And that underperformance costs investors their dreams.

The chart below shows overvalued stocks, the kind that growth investors buy, performed 26 times better than value stocks. Even companies without earnings did slightly better than traditional value stocks.

This chart is again based on data from Dr. Ken French. He co-authored many articles with Nobel Prize-winning economist Dr. Eugene Fama.

This dataset is incredibly useful when analyzing investment factors such as growth or value.

Your question might be: “If growth is so much better than value, why is value so popular?” The answer is that growth is more difficult to follow.

Value investors buy stocks that appear to be cheap. That’s comfortable to do.

Growth requires buying stocks that are doing well and expecting them to do better. History shows that’s the way to invest.

P.S. There’s a reason I’m bringing all of this up now, and I’ll reveal it in a free presentation later this week. Click here to sign up for it now.

Michael Carr, CMT, CFTe is the editor of two investment trading services — One Trade and Precision Profits — and a contributing editor to The Banyan Edge. He teaches Technical Analysis and Quantitative Technical Analysis at the New York Institute of Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MichaelCarrGuru.