The message that Americans don’t want to take interest rates into negative territory seems to have fallen on deaf ears when it comes to former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke, who just this week endorsed the monetary policy as a potential tool to be used by the central bank to fight a recession.

While delivering the American Economic Association Presidential Address on Saturday, Bernanke argued that negative interest rate policy (NIRP) should never be ruled out by the Fed. Here’s his own summary of the message, per Brookings:

“The Fed should also consider maintaining constructive ambiguity about the future use of negative short-term rates, both because situations could arise in which negative short-term rates would provide useful policy space; and because entirely ruling out negative short rates, by creating an effective floor for long-term rates as well, could limit the Fed’s future ability to reduce longer-term rates by QE or other means.”

Bernanke’s take on negative interest rates fly in the face of conventional wisdom around the world, though. Sweden’s Riksbank ended its five-year subzero rates experiment last month in what Bloomberg columnist Brian Chappatta claims was “widely interpreted as a message about the damage that can come from keeping yields suppressed for too long.

“In Japan and the euro zone, institutional investors have been forced to either buy riskier assets or accept exposure to currency fluctuations,” Chappatta continued in his column.

Minutes from the Oct. 30 Fed meeting, where the central bank cut rates for the third time in 2019 to a range of 1.5% to 1.75%, echoed some of the same reservations.

“Differences between the U.S. financial system and the financial systems of those jurisdictions suggested that the foreign experience may not provide a useful guide in assessing whether negative rates would be effective in the United States,” the minutes said.

Chappatta calls Bernanke’s comments “tone-deaf,” citing the Fed’s stated objective of “price stability and moderate long-term interest rates” that promote maximum employment.

Is it so bad, then, for the central bank to communicate “an effective floor for long-term rates” by ruling out going negative? Especially if that floor is close to zero? By contrast, I’m not sure anyone would categorize the German 10-year yield of -0.3% as “moderate,” in any sense of the word.

The idea of going to negative rates could already be dead in the water, at least in the short-term, as the Fed has already signaled that it aims to keep interest rates steady throughout 2020 barring any drastic economic shifts.

And Chappatta isn’t the only one that sees the problems surrounding NIRP. We’ve run many stories here on Money and Markets that voice similar opinions from the likes of Jeffrey Gundlach, Peter Schiff, Howard Marks and Gerald Celente.

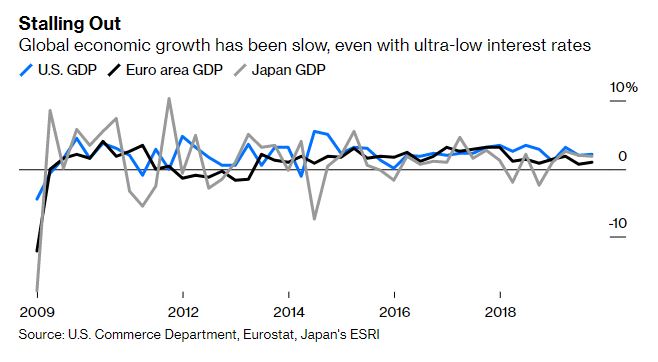

But future GDP growth could change the Fed’s plans in the coming decade.

“We’re still seeing no significant increases in estimates of productivity growth, in estimates of trend GDP growth,” New York Fed President John Williams said during last weekend’s conference. “We have come to the realization that these factors are basically the hand we’ve been dealt for the next five to 10 years.”

Chappatta thinks current Fed officials are “leery of negative interest rates,” but Bernanke’s call “is probably just cautioning current and future central bankers to never say never.”

But the columnist thinks the Fed should just stick to the plan.

“The evidence is just too flimsy at this point to conclude that the benefits of negative interest rates exceed the costs,” Chappatta wrote.

Only time will tell if NIRP is really dead or not, but Chappatta thinks that Bernanke’s comments could one day “be looked back on as one of the last gasps of the unconventional monetary policy.”

Read Chappatta’s full column on Bloomberg here.